At least a few times per month, someone will shoot me a message asking some variation of the following question:

“You had a great record in boxing. Why’d you quit after only one loss?”

[Learn more about my one loss by reading 8 Lessons from losing a fight on national T.V.]

I find this question interesting because I’ve yet to have one fighter ask this. They intuitively know and understand everything that I’m about to explain in this article about the boxing world and the life of a fighter.

For everyone else who is generally curious about the challenges of being a fighter and more specifically, is curious as to why I stopped fighting with only one loss, then read on and learn why I stopped boxing.

1) I make more money writing than most fighters

For my first 6 fights, the most money I made was $792 dollars on local club shows. When I got signed to a promotional deal with Roc-Nation sports, I started earning mid-four figures a fight.

For most of my fights, I made less than $5k for a fight. In the only fight I made more than $5k on, I didn’t earn more than $9k. I had 15 fights in the heavyweight boxing division—the highest paying division in boxing—and never once earned five figures.

Throughout my 18-month professional contract, I was paid a monthly stipend of $1000. By the way, all of the numbers I’ve given you are before taxes and trainer fees. If that doesn’t sound like a lot, keep in mind that my numbers were higher than most because I fought in the heavyweight division, and that’s the only division where you can make some decent money without fighting for a title.

Fighters are protective of their contract numbers for many reasons. Some legitimately honor the terms of the non-disclosure agreement that almost every promoter makes a fighter sign. Even though I promised not to name any names–and I think I present myself to be trustworthy enough—many of the fighters I talked to refused to confirm the low numbers of dollars made.

Fortunately, many other fighters trusted that I’d keep their numbers confidential.

How much do boxers make?

First, understand that the fighters aren’t making money unless a fight is televised on a major network. The fight promoter has to pay for the venue, insurance, security, medical, and sanctioning fees. This is all before the fighters get paid.

Whatever the fighter gets paid, he will immediately lose approximately 15-25% to manager and trainer fees. This is all before he has to pay taxes. It is simply not possible for a fighter to make a living from his fighting earnings alone if he’s not signed to a promotional company. Promotional companies get the fighter on television. What follows is a very simplistic breakdown of how this game works.

Let’s say that a network (Fox, ESPN, DAZN, etc.) shows 12 fights yearly. Promoters (PBC, Top Rank, Golden Boy, etc.) know that the networks have more money to put behind a fight; this is how their fighter gets publicity, so promoters compete for those dates to get their fighters on T.V. for more money and more exposure.

There are more promotional companies than networks, so the networks get get to be picky about what promotions get to fight their fighters on television. Likewise, there are more fighters than promoters, so the promotion company gets their pick of which fighters they want to represent. The money isn’t great even with representation unless you’re fighting for a major title. Even then, here’s something for consideration:

The better you get, the fewer times you fight up until you’re champion and fight about once a year. This article from Bloody Elbow breaks down how the money is distributed, but some interesting conclusions can be drawn from this data.

On average, a boxer only makes $67,948/yr. That’s not too bad until you see that the median salary is $2000. If the impact of these numbers is lost on you, I’ll use a simple example to demonstrate how lopsided this is:

Let’s say you’re with a group of 10 friends, and all of you make $20k a year, so your group’s average and median income is now $20k. Then one of you meets Jeff Bezos, and he becomes your friend. Well, now the average income of your group is MUCH higher, but the median income remains the same.

This is exactly what happens in boxing. Big-money fighters like Canelo Alvarez and Anthony Joshua raise the average, but most fighters barely make enough to cover training, let alone make a living.

I just talked to a friend who fought on television in the big money division, the heavyweight division. He made $55k. His next fight is guaranteed $100k. That sounds like a lot of money until you remember that he not only has to pay his trainer 10% (he doesn’t have a manager), but he’ll be taxed as a self-employed person, so he’ll owe the government 30% of that.

To put this in perspective, I clear $100k with relatively little effort, all online, without permanent physical damage. I’m also doing it in a way that helps many more people than myself (more on this point later in the article).

Don’t get me wrong: I don’t mind the hard life of a fighter. I did it for over a decade. I just wouldn’t do it if I had a safer alternative.

2) I got tired of being in constant pain

"Sure there have been injuries, and even some deaths in boxing, but none of them really that serious..."

— Ed Latimore (@EdLatimore) April 30, 2019

-Alan Minter

I didn’t get injured nearly as much as some guys I know, nor were any injuries particularly severe. Remember: boxing has actually claimed lives, even in the modern era of tighter safety protocols and more cautious refereeing. This never scared me, as I figured that I was going to die anyway—the difference is that when I go, I’ll have cool stories and memories.

"Don't you want to take a leap of faith? Or become an old man, filled with regret, waiting to die alone."

— Ed Latimore (@EdLatimore) February 25, 2021

-Saito, "Inception"

Boxing quickly teaches you the difference between being “hurt” and “injured”. Both conditions result in discomfort and pain but aren’t the same.

You can continue to train and fight through being hurt. It’s merely a matter of pain tolerance. Sometimes it’s intense but not debilitating.

Injury is debilitating. Injury is an actual change in your condition that prevents performance. You can’t do anything through injury.

Throughout my 12-year career, I only suffered four injuries, 2 of which were major concussions. I consider anything that forced me to stop competing as a major injury. One was a hyperextended elbow from throwing the jab incorrectly. I needed six weeks off and a little physical therapy. The second injury was much more severe. It was the first of two orbital blowout fractures I suffered during my boxing career. This required surgery and four months off.

Though I likely sustained many smaller concussions, there are two, in particular, that side-lined me. I sustained one concussion in practice as an amateur. I got hit off balance and ended up falling so that my head hit the canvas before the rest of me did when I fell. I was out for about a week and had to pass a concussion protocol before the group that sponsored me would let me spar again.

I was a professional fighter the second time I got a major concussion. I got hit so hard in sparring that I suffered the second blowout fracture of my career. This time it didn’t require surgery.

I sustained my second concussion while I was a high school physics and math tutor. I remember having trouble trying to help a student solve a basic math problem. I had also been making $10k+ per month writing, teaching, and using my mind. This was the first time boxing put my major earning asset in jeopardy.

I was already popular and paid for my writing. Given what I’d earn in a fight and the hours I had to invest to get it, the cost of boxing began to severely exceed its value. Boxing made sense when I was broke and had no other prospects for a great life.

Now that I can hop on the internet and sell a product that would make $10-20k in a week and people are genuinely interested in my writing and what’s in my mind, making a living putting my body at risk simply no longer makes sense.

3) The lifestyle and time commitment

As an amateur fighter, I earned a state title, a national title, a paid sponsorship, and a #4 national ranking. As a professional, I was represented by Jay-Z’s Roc Nation. I bring these stats up not to brag but to demonstrate that I know what it takes to perform at the top level of this sport.

I used to say that in my next life, I’m going to be a musician or a rapper because as a fighter, you don’t really get a chance to cut loose and enjoy the (small) fruits of your labor. Sure, some guys go out and drink and party and still have success, but they absolutely pay for it.

For every guy who makes it despite drug, alcohol, and lady problems, there are hundreds—if not thousands—of careers that are cut short, ruined, or are never even really started because a fighter couldn’t control his vices.

How much time does it take to become a professional boxer?

No one “plays” boxing. Mike Tyson famously referred to it as “the hurt business.” I truly believe that boxing is something that you have to dedicate your life to.

When I fought, I thought I could do other things besides fight, which perhaps caused me not to go as far as I could. However, even while attending college and serving in the military, I dedicated 35-40 hours a week to training. [Learn about my boxing training routine here]

I trained roughly that amount of time for both my amateur and professional career. This meant taking low-paying or odd jobs, as those were the ones that allowed me to keep up my training schedule. During my time as a boxer, I was a:

- Starbucks barista

- Americorps Volunteer

- A security guard at a homeless shelter (working nights, still training during the day)

- Bank teller

- T-Mobile sales rep

- Lab rat. I did phase 1 trials where they test new drugs on you for money

- In the Pennsylvania Army National Guard

- Outright unemployed for stretches of time

One of the hardest parts about being a fighter is that there is no support while you’re working to improve your craft, especially if you start as an adult, where you’re expected to be able to pay your bills and live on your own.

When you start as a kid, this isn’t really an issue. But to go anywhere as an adult, you will make sacrifices of time, and those sacrifices have an opportunity cost.

At this point, my lifestyle consists of content creation, speaking, and traveling. The last one is mostly a hobby, but it’s something that I always wanted to do when I was younger, and now I can. I’m not interested in giving that up. I can also have a greater impact on the world in this capacity. Because I try to produce helpful and useful content on the internet, I have a greater reach than I might ever have with boxing.

In short, this lifestyle is far more purpose-driven than boxing. It’s also a lot less painful.

4) I am too small to be a heavyweight boxer

I spent my entire amateur and professional career fighting as a heavyweight. The minimum for this weight division is 201 lbs and there is no maximum. Because there is no weight limit, the tallest fighters tend to be heavyweights.

I’m 6’1”. For most of my amateur career, my weight hovered in the mid 220s. As a professional, I typically went into the ring between 215 and 220. Both of these numbers make me a very small heavyweight.

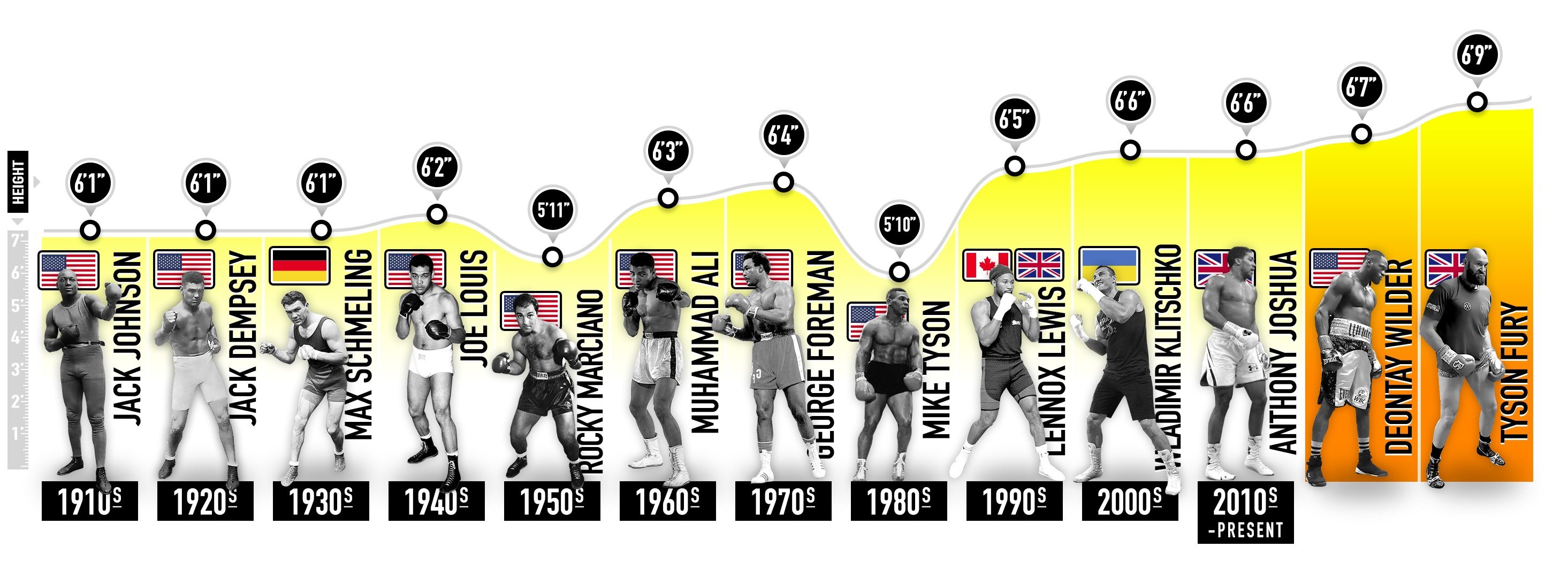

According to some roughly crunched numbers by a poster on boxrec.com, the average height of a heavyweight boxer since 2010 is 6’3.6”. The poster’s math is crude and doesn’t reveal that this is likely skewed to the left, meaning that the average height is shorter than the median (most frequently represented) height.

In other words, not only am I shorter than the average height, most heavyweight boxers are taller than the calculated average of 6’3.6”.

To better illustrate this, I’ve referenced an article aptly titled “The Evolution of the Heavyweight Boxer.”

“As the research shows, there has been a steady increase in the height of heavyweight champions from the early days of Jack Johnson in the 1910s up to the current climate, which will soon see two mammoth competitors Wilder and Fury collide.

Without an upper limit, heavyweights have simply got bigger and bigger throughout time, and the age of the ‘super-heavyweight’ evidently began around the 1990s when giants such as Lennox Lewis entered the fray.”

What’s the problem with being a shorter heavyweight boxer?

While I had a great amount of success at 6’1”, it became clear to me that the height disadvantage was going to soon become one I couldn’t overcome. I compensated for being shorter with speed, power, and conditioning, but those tools quickly became nullified as my opponents got more skilled.

While it’s theoretically possible that someone my height could have success, the reality is that when your opponent is just as skilled as you are, physical attributes make a big difference. This doesn’t say anything about the fact that it’s easier to be mobile and athletic at 6’5” 240 lbs, compared to a guy at 6’1” carrying that same weight.

If I could do things over again, I would have dropped to cruiserweight, the weight class below heavyweight. I would have automatically been above average in height and weight. There would have been less money, but I would have had a longer and more successful career.

I came to the conclusion that even if I could get into the top 10, as a heavyweight, on one of the many ranking lists for the belts, it would cost a significant amount of energy and time to get there and I’d almost certainly lose to someone. Losing would make me a journeyman fighter.

The money isn’t terrible, but I make a lot more creating content and selling info products. And I don’t have to suffer injury.

5) I have no desire to be a journeyman or an opponent

In 2013, I made three decisions that completely changed the trajectory of my life: I stopped drinking, enlisted in the army, and went back to school. This seems like a crazy workload, and it was.

My coach couldn’t stop my decisions, but he was not a fan of them at the time, for a good reason: they took away time from training. However, I saw the future.

I knew that one day, boxing would be taken away from me. I’d either get injured, or I’d lose a fight and be forced to become a journeyman/opponent.

Journeyman/opponents are fighters who will never fight for a significant title, but they’re good enough to be used as a test for upcoming fighters with perfect records. While most journeymen don’t enter the ring with the intention to lose, the promoters and matchmakers know that this is the likely outcome, and it is exactly what his job is.

That’s not the life I wanted because, to me, it was picking one of two miserable paths: either I’d win a few fights and lose a few fights for $10-20k paydays or I’d lose most of my fights and eventually end up only making a few hundred dollars per fight.

Too much pride, self-respect, and opportunity to lose fights for a living

I have too much respect for the sport of boxing to half-ass it, so I’d be back in a position where I’m in the gym for 30-35 hours a week, but I’d be in extremely difficult fights where I’m a significant underdog.

I went and got a physics degree and enrolled in the military to have more options in my life. I started this blog and a social media presence so I could have more options in life. I did not do all of that to effectively be a punching bag for a few extra grand.

Plus, the cool thing is that having that record continues to open up doors for me. It’s a lot easier to introduce me as a potential guest on a podcast or show when my record is 13-1-1 instead of 13-6-5 or something to that effect.

In summary

I stopped boxing because I’d realistically gone as far as I could with my physical attributes and figured out how to make a lot more money with much less damage to my body. I’ve also developed a lifestyle that makes training difficult.

I enjoyed my life as a fighter and am extremely grateful for everything I got from boxing. With that said, I have no interest in fighting anymore and I’m having a bigger impact on everything else that I do.

Boxing Lessons on Grit, Resilience, and Antifragility

In this e-book, I teach you 20 mindset lessons I learned from my 13-1-1 professional heavyweight boxing career.

Use these to conquer any challenges you face, in the ring or in life.

Learn how to develop the mindset of a fighter, from a fighter, so you can win the battles you face.