People always think I’m full of it when I tell them that learning how to box helped me get a degree in physics, learn enough Spanish to watch my favorite telenovelas *mostly* without peaking at the subtitles and get my chess rating into the 1800s, Everyone has this idea that boxing is a sport of brutal headbanging aggression that leaves you with less mental capacity than when you started.

And to be fair, I have had some concussions that left me at a loss for how to do something as basic as finding the roots of a polynomial—that happened after a brutal thumping I took from one Cassius Anderson during a sparring session.

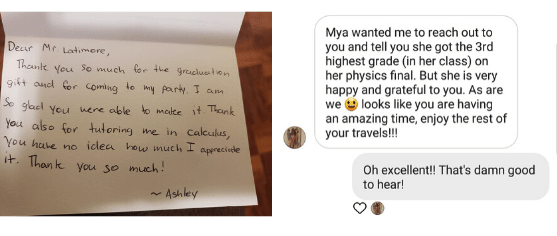

The following day, I was meeting with a high school student I was tutoring. While working on her Algebra 2 homework, I drew a blank when recalling the relatively simple method for finding the zeros of a quadratic equation.

Still, it eventually came back to me, and I haven’t had any other lapses since.

I’ve been hit by a lot of guys in my boxing career—even by some future world champions—but no one quite hit like Cassius. Cassius broke my orbital bone in sparring.

I actually had the same injury before in the other eye, and it was when former IBF champion Charles Martin hit me in a sparring session—and when it happened then, I needed surgery. But Charles didn’t hit me hard enough to give me a concussion that made me forget my math.

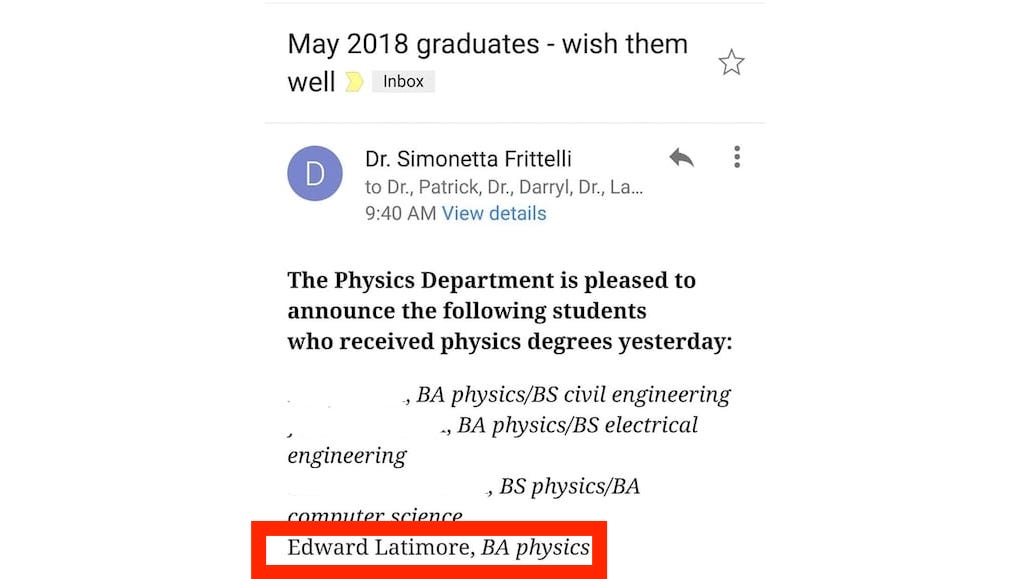

People think I’m full of it mainly because how many boxers do you know that have gone on to get a degree in physics—especially as adults after they did not graduate from high school? I’ll wait. No, seriously, I’ve asked this question on other social media, and if you know any other boxers who have done it, have them shoot me a message.

For anyone reading this who happens to remember me from high school, I was allowed to walk with the class at graduation, but I never *officially* graduated from Schenley High School.

For anyone reading this who happens to remember me from high school, I was allowed to walk with the class at graduation, but I never *officially* graduated from Schenley High School.

To make a short story shorter, my grades sucked. When I was offered a chance to make up for failing senior English—the one class students in my school district are required to pass to be allowed to graduate—I got caught plagiarizing an essay and failed summer school, too.

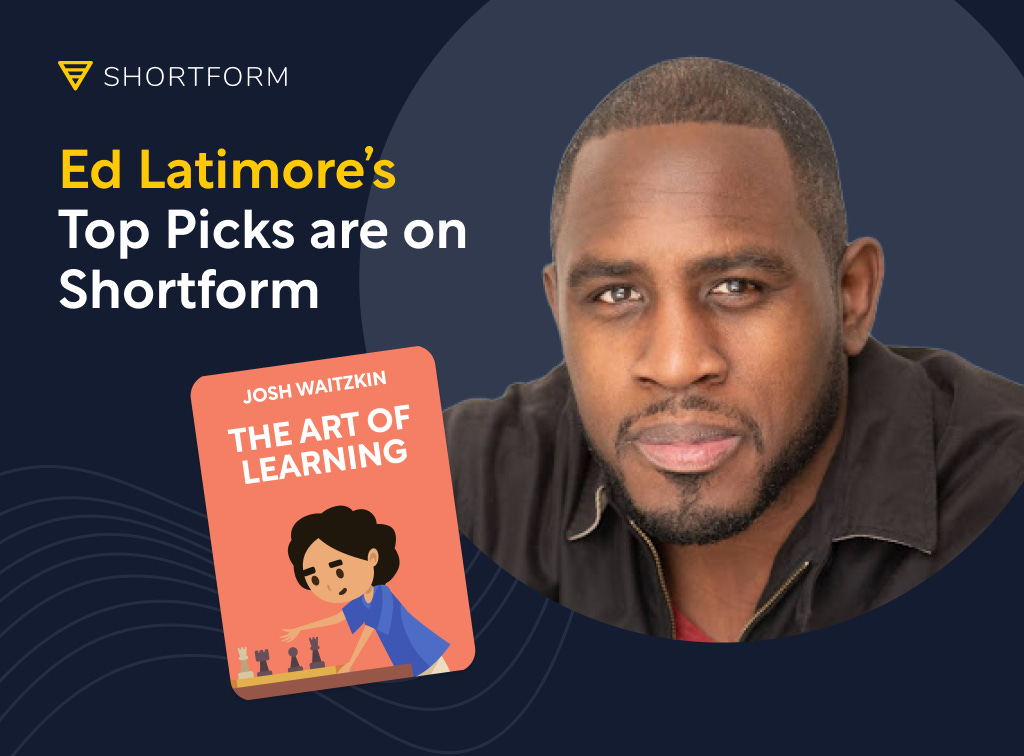

This is a great place to mention the sponsor of this essay, Shortform.

I would have been a much better student if I had something like Shortform in high school. Shortform is a book summary platform where you can get detailed summaries of over 1000 popular non-fiction books.

I’ve always been skeptical of book summary services like this because I figured people wouldn’t need to buy the book if they had the summary, robbing the author of their rightful compensation. I later learned people don’t use book summaries instead of the actual book.

I’ve always been skeptical of book summary services like this because I figured people wouldn’t need to buy the book if they had the summary, robbing the author of their rightful compensation. I later learned people don’t use book summaries instead of the actual book.

It turns out that reading the summary of a book before, during, and after reading the primary main content causes you to understand better and retain more information.

The official name for this is Schema Theory, and I’ve taken advantage of it by using Shortform’s detailed summary of used it to help me recall some ideas for this essay from one of my favorite books, “The Art of Learning.”

To check out Shortform, use my link shortform.com/edlati2 for a one-week free trial, and if you stay on with them after your trial ends, you’ll get a 20% discount on your subscription, but only if you use that link.

Anyhow, even though I failed English, that was mostly the result of laziness and burnout. My real nemesis in high school was math. No matter how I hard I worked, i could not get it.

Now, even though I did not technically pass high school, I was the recipient of some good old affirmative action and ended up in college where I was also a terrible student and, to make matters worse, I was big into the drinking and chasing girls thing. Ultimately, I failed out after 3 semesters.

For the next part of the story to make sense, you gotta know that my friends in high school were nerds. It’s a cool story for another video, but I went to a high school far on the other side of town, in a completely different socioeconomic level.

I was the beneficiary of positive peer pressure. I wanted to be like my friends, but I didn’t have the intellectual firepower—but I did a great job of hiding it.

Why was I so bad at school and math, though? There are a few reasons, but the biggest one was that I never had a foundation.

Well begun is halfway done

I did elementary and middle school at schools in the heart of the hood, and it was as bad as you can imagine.

We had metal detectors in middle school along with a uniform policy to keep the gang colors out, and in elementary school, we were doing active shooter drills before they were cool.

Let that sink in. A bunch of 9 and 10-year-olds were being drilled on what to do if the gangbangers got outta pocket, and some of the violence ended up at a damn elementary school, or they were shooting at the school bus.

It’s damn hard for a kid to learn in that type of environment—and that says nothing for the bullying I experienced while I was there too.

So, when I got to high school, I had no academic foundation and fell so far behind that I failed high school. This, of course, did a number on self-esteem when it came to my intellectual ability. I didn’t do anything for the four years after I graduated from high school besides make a bunch of failed attempts at community college and drink myself into a stupor.

But then I took up boxing at the age of 22. And I was terrible at that, too.

I was only beating guys on raw power and athleticism, but I wasn’t learning the sweet science of learning how to hit and not get hit. My footwork was trash, my punches were thrown with terrible technique, and my cardio was…not terrible, but it was subpar.

Once, in an amateur fight, I punched with such bad technique and balance that I knocked myself down. I could only beat guys if they had worse footwork than me, but anyone who moved out of the way and popped a jab out would beat me on points. I only had two losses for my first 15 or so fights, but all of my wins were by knockout, and my losses were on points. That’s not good. It meant I couldn’t box; I could only brawl.

But I told myself that the only way I’d quit was if I got injured because, at that point, I was a bit tired of just being a high school has-been whose only claim to fame was that I could get girls. I was just tired of being a loser so i figured that if I can’t educate myself to greatness, I’d fight my way there instead.

This decision to not quit was one of the most significant I’ve ever made, only behind getting sober and committing to my wife.

I became good enough to win the PA State Golden Gloves and finish in the quarter-finals of the national Golden Glove tournaments, finish in the semi-finals for the East-West trails, win the police athletic league national tournament, and go on to have a 13-1-1 professional career signed by Roc Nation sports.

All of this happened because I even learned how to box. I went from being a clumsy beginner to a graceful master, and when I went back to school at 30, I eventually earned a bachelor’s degree in physics—despite failing math in high school.

What did I do, and how can you implement these tactics to learn faster?

It’s cliche, but it all starts with mindset

Let’s start with mindset. I know it’s cliche, but it is more than saying, “Believe you can do it and set your mind to it.”

When it comes to learning and skill acquisition, there are—broadly speaking—two types of mindsets: fixed and growth. Stanford psychologist Carol Dweck popularized these in her aptly titled “Mindset: The New Psychology of Success,” and they’re exactly what they sound like

A fixed mindset is when you believe your abilities and skills are fixed. Whatever you start with is all you have, and you can only experience marginal improvement via practice.

A fixed mindset is when you believe your abilities and skills are fixed. Whatever you start with is all you have, and you can only experience marginal improvement via practice.

A growth mindset perspective is an approach in which you think you can get good at anything and acquire any skill.

Objectively speaking, it doesn’t matter which one is correct or has more evidence to support it. What matters is which one you believe because that will determine how much effort you put in.

The most powerful belief you can hold is that, given enough time and motivation, you can learn anything.

After I watched myself go from a clumsy brawler to a somewhat skilled national champion-caliber boxer, I figured that if I had done this with my body, there was no reason I couldn’t accomplish the same with my mind.

So now I had the confidence to approach math because I no longer believed I wasn’t a math person. Instead, I started to see myself as a person who could, if I worked hard enough, could master math.

But that meant figuring out why I was so bad at math in the first place. See, math is cumulative, which meant that my later difficulties started earlier in my education.

Very often, when people have difficulty performing an expected skill at the same level as their peers, the problem isn’t mindset or ability, but rather, they were never taught the fundamental building blocks or their skill set.

Because they lack this fundamental knowledge, their progress is limited because you can only go as far as your biggest weakness.

It didn’t matter how hard I hit guys because I never learned the fundamentals of boxing footwork. All my opponents had to do was move out of the way or viciously counterattack me. It wasn’t until I learned how to move my feet correctly that I could finally beat a kid who had bested me twice and win the Pennsylvania State Golden Gloves.

When I attempted school again, I drew on this experience and did a deep dive into my math knowledge to see where my fundamentals were lacking. When I realized that I’d never even learned grade school arithmetic correctly, I at least had a path.

You can go far on just the fundamentals

When you build a fundamental knowledge base of the skill you’re trying to learn, it can feel like you’re taking a long way, but I assure you that this is the fastest way to learn.

When you do things the right way from the beginning, you save time because twice:

First, when you don’t make any mistakes in the future, you have to go back and redo, and second, when you don’t ever have to slow down, you’ll go farther and longer without hitting plateaus.

So for many months, I did every basic math problem and watched every tutorial I could I find until I felt confident that my math skills were on point. Eventually, I got a test when, because I enlisted in the army at age 28 to get money for school, I had to take the ASVAB, and I scored a 99.

For those who don’t know, the Armed Services Vocational Aptitude Battery is the intelligence assessment test all incoming enlisted soldiers take to see which army jobs or “military occupational specialties”—often abbreviated to just MOS—a soldier is qualified for. It’s also used to assess if a candidate can even serve, i.e., does he score beyond a threshold?

Once I mastered math basics, I breezed through calculus, differential equations, and linear algebra. I also became a popular tutor for high schoolers taking physics and mathematics.

If you had told 18-year-old me, who had just failed high school, due mainly in part to his performance in mathematics, that I’d be helping kids pass the AP physics and calculus exams, I would have laughed at you. But alas, I stumbled into a $ 2000-a-week side hustle that was even more rewarding than it was profitable

The final thing that will speed up your learning is doing more learning. In a study by Robert A. Bjork and Elizabeth Ligon Bjork in 1992, two groups of participants were assigned to learn a list of words. One group stopped practicing after reaching a specific level of accuracy, while the other group continued to overlearn the words.

The final thing that will speed up your learning is doing more learning. In a study by Robert A. Bjork and Elizabeth Ligon Bjork in 1992, two groups of participants were assigned to learn a list of words. One group stopped practicing after reaching a specific level of accuracy, while the other group continued to overlearn the words.

The results revealed that the overlearning group exhibited superior long-term retention and recall compared to the group that stopped at the criterion level. Even after a considerable delay, the overlearning group displayed enhanced performance.

This type of learning and training is a monotonous grind, but I’m convinced that the only way to become proficient in anything is to practice to the point of boredom. Consistency and repetition only get you an invite to the audition. If you want the leading role, you need to know your craft so well that you don’t think about it but could never forget it.

If we take everything in this essay together, we can say that the best way to learn faster boils down to three core ideas:

- Well begun is halfway done. Or, if you prefer, measure twice, cut once.

- Shortcuts are the longest way to do anything worthwhile. The only real shortcut is the scenic route.

-

Don’t practice until you get it right. Practice until you never get it wrong. Then, practice some more.