I was never naturally good at math.

I failed calculus three times before the concepts finally sank in.

It wasn’t until after I learned some principles for getting better at math in general that I was able to pass the 4th time. I went from failing most of my high school math classes to making $1K a week tutoring students in math, chemistry, and physics.

Calculus is an entry point and prerequisite to learning higher levels of math. It’s also the most widely used form of math in the real-world beyond basic arithmetic.

For example, the algorithms that keep you watching more content on social media platforms are often based on calculus.

Calculus is the study of rates of change over tiny intervals of time. The problem is, though it has real-world applications, learning calculus is mostly about learning to use it in theory vs application. This turns off beginners and anyone who might have a natural inclination toward it.

The genius myth

Some people have a different set of mental faculties but what we think of as a genius is rarely inherent brain power. More often, genius is an uncanny/uncommon desire and ability to focus on a subject until it’s learned.

Einstein, Nobel prize winning physicist Richard Feynman, and Newton were all ordinary dudes with extraordinary curiosity. This holds true outside of math and physics as well.

Johann Sebatian Bach famously stated his true talent in music was an inclination to work hard. Some of you might remember the movie Searching for Bobby Fischer. It was based on the childhood chess master, Josh Waitzkin. Though revered as one, Waitzkin has since written books about how he wasn’t a genius, but he was a curious, thorough learner.

I tell you about these things because even so-called geniuses realize that the biggest hurdle is actually believing it can be done. And your capabilities can blossom from there.

For many students, that mindset shift happens alongside practical support—whether through tutoring, structured practice, or even a trusted essay writing service that helps reduce academic overload while they focus on mastering difficult subjects like calculus.

Learning calculus today doesn’t mean you’ll start Space X 2.0. You don’t have to be destined for MIT or even a career as a mathematician. You simply have to develop a growth mindset around math.

Anyone can learn calculus and the following sections will show you the easiest way I know how. This article won’t focus on the “how” of calculus. It will focus mainly on the “why” and the “what”.

Despite the title, I’m not teaching you how to take a derivative, integral, calculate a serious or any of that. I’m showing what that stuff means, simply, so you are much better equipped.

Hopefully you won’t just understand calculus better, but you’ll excel at it.

The fundamental, simple, main idea of calculus

One of the things that finally made calculus click for me was when I finally understood the “why” of the subject. This is a lot different than the “how” or the “what.” I’ll explain.

Most students go through calculus and all they learn how to do is take the derivative or integral or figure if a series converges or diverges, but they have no idea why we do it. They have a vague notion of why its important, but most of that boils down to “this is a required class” and “smart people do this, so I must do it to.”

Even if they’re motivated by the outcome (like getting a high paying job), they won’t enjoy the process because they have no idea why they’re doing or even most times, what they’re doing. They’re just repeating methods and not thinking.

Well, after taking calculus 4 times, here’s what I figured out on the 4th try that got me no lower than a B afterwards: calculus is the math we use to measure things that are changing. Whether that change is growth, decay, expansion, or contraction. Calculus is the math we use to plot, predict, calculate, and solve those changes.

Arithmatic and geometry are insufficient because they only use “constants.” This means that they remain constant in the formula or calculation. This isn’t good for things that change, which is why calculus requires such strong grasp of algebra, where “variables” are used.

Once you understand the “why” of calculus—to measure and calculate change along with all of the implications of that change—then everything makes sense.

Learn the parts

Learning calculus is like the next steps in language learning. You’ve gotten the basic words and sentences down when you learned Algebra and other prerequisites. Now it’s time to write essays and fit larger concepts together. The first thing to know about solving calculus problems is that there are basically three main segments of calculus:

- Limits

- Derivatives

- Integrals

Doing these techniques is relatively simple, though not necessarily easy. In fact, the a large portion of Calculus II is learning different integration techniques and recognizing when to use them.

With that said, understand why you need them will go a LONG way in helping you proficiently use them all.

How limits work

A great technical definition of a limit is “A limit describes how a function behaves near a point but not at that specific point.” What exactly does this mean and how does it help understand the “why” of calculus? More specifically, why do we need to understand how functions behave near a point to do anything?

First, a simple, brief, and mostly precise (though entirely accurate) definition of a function: A function is a formula that has only one output for every input. Mathematically speaking, functions have one “y” for every “x.” You may also remember the vertical line test. As long as you can only pass a vertical intersects a graph once at every point along the graph, it’s a function.

Another important point about functions, and this may be obvious and seem redundant, but it’s important to understand why limits are useful and powerful: functions tell us what happens as the inputs change. You can create a function for anything:

- The time it will take to make a trip. Input (x axis) is your speed. Output (y axis) is the time.

- The money you make it. Input (x axis) is what you do to get paid (hourly, event, commission, etc.). Output (y axis) is what you earn.

- The height of water in a bathtub. Input (x axis) is rate of running water. Output (y axis) is amount in tube

Any past or present calculus students reading those examples will recognize the examples and either shed a tear of nostalgia or a stretch of frustration.

With that out the way, let’s recall the main idea of calculus: a math to work with changing quantities. Knowing how something behaves exactly at a point doesn’t tell us anything about how it got to that point OR what it will do after.

Does it speed up, slow down, stop entirely, or make a quantum leap or drop? Is it even possible for it to make it to that point?

Limits allows us to figure out the behavior of something as it approaches some fixed point. We can use that behavior to get the most precise measurement of something’s output based on *changing* inputs.

Think about airplanes.

Almost all commercial flights use autopilot for landing. The computer needs a formula to calculate what to adjust the plans speed to, every second, as it approaches the fixed point of the airport. Humans do this by feel along with help from instruments. Computers use an equation (a bit more complicated than a limit, but the building block idea still remains).

Limits form the foundation of calculus and help us predict an unknown number to a reasonable level of closeness—best speed for the airplane at any moment as it approaches the airport. Otherwise, the computer would be left to guess (since it can’t go by feel or sight) and that would be disastrous.

How derivatives work

From now on, every time you hear the word “derivative”, I want you to replace it with “change.” From now on, whenever you see the derivative notation , think “division of a quantity.” This is not entirely precise, but it’s precise enough to be useful and help you think about calclus in a useful manner.

And more importantly, it’s accurate. The definition of derivate is “the rate of change of a function with respect to a variable.”

“Derivatives measure the slope of a curve at a given point, called a tangent line.” This is all many of us are told, but what does that mean?

I used to think “slope of the tangent line” meant the slope of the line that touches the function at that specific point. “Tangent” roughly means “touch.” When I realized it’s the slope of the line made by the tangent of the angle between that line and the x-axis, calc opened up.

And what are slopes? Just rates of change. Recall your algebra days where you learned “rise over run” or, more mathematically, “(y2-y1)/(x2-x1).” It’s how the output changes with respect to the input. The steeper the slope, the greater the rate of change.

**Since the value of “x” can change at any given time, you’re actually dividing changing quantities. This is why I say that derivatives are about multiplying things that aren’t constant. **

It’s key to remember that derivatives measure change with respect to a variable. This is fairly straight forward when there is only one input (variable), but things become *slightly* more complicated when you reach multivariable calculus or differential equations.

Still, this idea is a strong start. This a great site to help you calculate derivatives.

How integrals work

Let’s start simply and build from there.

The opposite of division is multiplication. You can get back to the divisor (in fraction form, the numerator) by mulpliying the quotient (the answer) by the dividend (in fraction form, the dividend). In this way, you undo a division problem with multiplication. The inverse is true as well; multiplication problems are undone by division.

Let’s apply this calculus.

If derivatives are the division of changing quantities, then to “undo” them, we have to use some operation that is the multiplication of the derivates quotient and dividend. In this case, we need the multiplication of changing quantities. We call this the “Integral.”

The name tells you exactly what the integral does. “Integral” is from an old latin word meaning “forming a whole” or “whole.” This is exactly what integrals do. They put back together the division done by differention.

They’ll teach you that integrals are used to calcuate the area under the curve, volume, and probability. All of that is true, but it doesn’t fundamentally tell you what they do. Those are just applications of it. I believe that if you understand the “why” and “what”, the “how” is child’s play.

Integrals allow you to figure out totals. Those totals can tell you if something is converging or diverging, how much space you have based on changing parameters, and there are many applications to sound and light that make today’s entertainment and ease of life possible.

The Fundamental Theorem of Calculus

Understand the purpose of the three tools of calculus brings us to the fundamental theorem of calculus. I’ll formally state it, but if you got the last section, you understand everything about calculus.

You think I’m kidding? The theorem of calculus says otherwise—both of them. Yeah, there are two, however I’m only going to go over the first one because it’s the most important:

“Let f be a continuous function on the closed interval [a, b] and let A(x) be the area function. Then A′(x) = f(x), for all x ∈ [a, b].”

If you don’t speak math, this translated says “if a line called “f(x)” passes the function test between two points “a” and “b”, then there is a deriviate that exists for every point between a and b, and that derivative has an integral.

It’s the fundamental theorem of calculus because this is ALL CALCULUS IS. It took me failing calculus 3 times before I understood that. Hopefully, now you don’t have to.

The nootropic I wish I had while studying physics

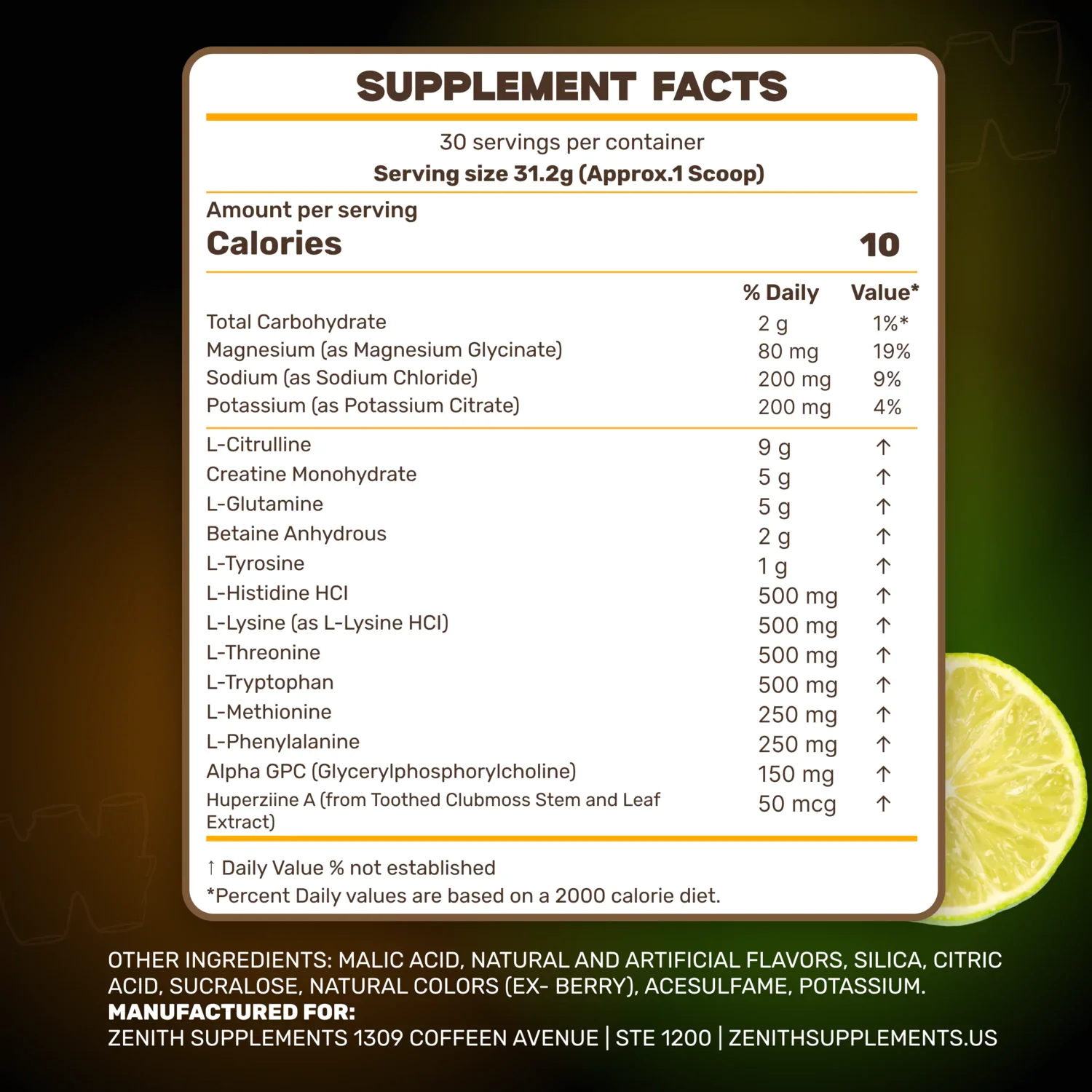

Let me tell you about living between textbooks and training camps – as a pro boxer studying physics while serving in the military, I know what it means to need peak performance in both body and mind. I could have gotten Morning Would back then..

This firefighter-created formula doesn’t just wake you up – it provides the nootropics to tackle complex calculations, amino acids to maintain fighting strength, and electrolytes to keep you sharp through marathon days. I drank a lot of coffee, but when you’re solving differential equations between sparring sessions and PT, you need more than caffeine.

You need something that supports both mental acuity and physical performance. Morning Would is built for those who refuse to compromise on either

Whether you’re challenging your mind, body, or both, this is a can’t-miss supplement.

Write the steps

All learning will involve some rote, repetitive memorizing. But to study calculus more thoroughly, you’ll need to take it a step further.

Nobel prize winning physicist Richard Feynman knew that if he could break down a subject to its most important concepts, he could learn it. His method was later dubbed the Feynman technique. Anyone can use this technique to better understand and study any topic.

The Feynman Technique

- Take out a sheet of paper and at the top write down the concept you are trying to understand

- Explain each step in the concept as if you are teaching it to someone else. Go back to class notes or reference materials to further explain tough concepts.

- Simply the language and/or use an analogy to better understand and visualize the important concepts

- Work through the technique to test yourself for understanding without referring to your notes or class material.

To use this technique to learn calculus, you’ll need to use practice problems to work through each step. It’ll help you grasp the concepts behind limits, derivatives, and integrals while also working through practice problems.

For more thorough learning, you can also read my easy 4-step process for problem solving. It’ll help you better understand any problem you come across.

In my studies, I found working through problems then usings a tool like Khan Academy helps to check my work. It helped me understand where I went wrong and correct my mistakes for other problems.

Here’s a warning though—don’t cheat. Taking the easy way doesn’t form the necessary neurotransmitters in your brain for deep work. And the sooner you learn to use your brain to figure out hard things, the better.

Don’t rely on class alone

Calculus class should be an intro to new important concepts and to clarify what you’re learning. You shouldn’t be relying on it to do your learning for you. In high school, your teachers will go at your pace until you learn. Calculus courses in college leave it up to you to do the heavy-lifting of learning.

If you feel like you are floundering, find a good tutor. Good tutors are often those that struggled to learn, like me, and figured it out. Which means they can help you figure it out also. They can also teach you how to calculate calculus graphs and functions without becoming handicapped by a graphing calculator.

In the real-world, calculus is used in financial market predictions and places like computer science. It can be difficult to understand by theory alone. For example, the way mathematicians like Leibniz learned isn’t how we learn today, which focuses more on the fundamental theorem of calculus and not how to use it.

And because theories can muddy the practicality of a tool, you need to seek help and use practice problems outside of the classroom.

…which brings us to the next point.

Repeat, repeat, repeat

Math is not a subject you can coast on learning through listening. You need hands-on work to grasp the important concepts and usefulness. Now, you probably won’t be using trigonometric identities or differential equations on a regular basis in life. But learning to work through these concepts can teach you about yourself.

When you learn something difficult, you learn perseverance and confidence. These attributes carry on throughout life and become a reference point for self-improvement.

Put simply, get more practice with more problems. Books like Calculus by James Stewart (in any addition) is full of practice problems you can work through over and over.

Use your accumulated knowledge

Calculus ties together other areas of math that you usually learn first. For example, calculus finds equations in nature then uses algebra to solve them.

Math learning typically flows in this manner:

- Addition, subtracting, multiplication, division

- Algebra

- Geometry

- Trigonometry

- Calculus

Calculus is really Algebra’s big brother. Many of the concepts that seem so daunting are sequences of algebraic functions. When you know how to properly break down fractions and polynomials you’ll have an easier time with calculus.

Before you get to calculus, you usually take a prerequisite called precalculus, which is a more advanced version of Algebra. Master your prerequisite learning, and calculus will be easier to grasp.

Wrapping up

Now, you don’t have to be a mathematician, but with these tips you can get good enough at calculus to pursue a career or simply to pass your calc tests.

Here’s the short version of how to learn calculus (the easiest way I know how):

- Develop a growth mindset. If it can be learned, you can learn it

- Understand the parts of calculus and what it seeks to accomplish

- Write the steps thorough and simply, then refine them further

- Don’t rely on calculus class to do your learning for you, get help

- Practice approaches perfection

- Learn your prerequisites

If I can go from seeing dead bodies in the hood to becoming one of the top performing physics students in the country, you can learn calculus.

I hope that helps.

The rest is up to you.

Learn the method I used to earn a physics degree, learn Spanish, and win a national boxing title

- I was a terrible math student in high school who wrote off mathematics. I eventually overcame my difficulties and went on to earn a B.A. Physics with a minor in math

- I pieced together the best works on the internet to teach myself Spanish as an adult

- *I didn’t start boxing until the very old age of 22, yet I went on to win a national championship, get a high-paying amateur sponsorship, and get signed by Roc Nation Sports as a profession.

I’ve used this method to progress in mentally and physically demanding domains.

While the specifics may differ, I believe that the general methods for learning are the same in all domains.

This free e-book breaks down the most important techniques I’ve used for learning.