Today’s newsletter was inspired by the following post on FB.

When this came across my timeline, I immediately responded:

“This is why 43% of Americans are obese, and all the top causes of death are metabolic syndromes. And most can’t cover a $1000 emergency. And the stats on antidepressant use…”

This response rilled some people up, but here is a hill I will die on:

Humans are antifragile creatures.

The word “antifragile” was coined by Nicolas Taleb to describe systems that improve after disruption. The basic idea is that there are three levels of stress response:

- Fragile. The system breaks under stress. A glass is fragile because it easily breaks when you drop it.

- Robust. The system resists stress. A plastic cup is robust because, while it’s possible to break it, it will take a lot more than hitting the ground.

- Antifragile. The system comes back strong after being stressed. Bones come back strong after being exposed to stress.

Yes, it’s possible to break a bone. Bones break all the time. However, an appropriate amount of force applied to a bone beneath its breakpoint will cause the bones to adapt and better resist stress in the future.

The same idea works for our muscles and immune system; we lift weights to get stronger, but not so heavy that we can’t move them. After we get sick, we develop resistance (and, in many cases, outright immunity) against the strand of a pathogen, but only if it isn’t too devastating.

[Note: I know this is a gross oversimplification of immunity, but it is correct enough to make decisions that will mitigate negative outcomes. Anyone on my mailing list over 35 remembers chicken pox parties.]

Our physiology is antifragile, and we start there because it’s the easiest place to see how this concept applies to the real world. I love Taleb as much as any pseudointellectual, but this idea would only be an academic theory and exercise in mental masturbation if there weren’t real-world examples and applications.

The antifragile model also predicts what happens if an antifragile system is NOT exposed to stress.

When astronauts spend extended time in space, their bones weaken and must slowly be reacclimated to Earth’s gravity. In hospital patients who have been bedridden for long periods, muscles must be built back up before they can walk again.

One of my favorite books, “The Epidemic of Absence,” demonstrates that food allergies and asthma increase as a country’s GDP rises and becomes cleaner. Without parasites and pathogens to ward off, the immune system becomes less able to deal with incoming threats and overreacts to what is otherwise healthy.

Psychologically, humans are no different.

In “Coddling of the American Mind,” Dr. Jon Haidt makes the argument that the mental health crisis wreaking havoc on younger millennials (birthday 1989-1996) and Gen Z (anyone born after 1997) is driven by them not being exposed to emotional hardship, pain, and risk while growing up. This crisis is due to what he calls “Three Great Untruths.”

- You must strive to avoid bad experiences at all costs

- You must always trust your emotions over reason

- The world is a black-and-white battle between good people and bad people; there is no in-between

If you strive to avoid bad experiences, you won’t be able to handle bad experiences. Life is hard and full of unpleasantness. The idea that it should be easy or fun is a relatively new notion for humanity.

Consider the following timeline. In considering this timeline, let’s focus on mainstream archaeology (i.e., I think Graham Hancock makes compelling arguments, but they aren’t necessary for the point I’m making):

- Homo sapiens, the species of human that you and I belong to, evolved roughly 300,000 years ago.

- The last ice age ended about 12,000-10,000 years ago.

- Farming began shortly after, estimated between 9000 and 10,000 years ago.

We aren’t done yet, but I need to point something out.

Before farming, humans ate by hunting, fishing, and foraging. They weren’t going to the refrigerator to grab a pack of steaks to thaw. Wherever they wanted to eat, they had to hunt and kill it. Anyone who’s hunted or fished knows how long it can take, and that’s with modern firepower and technology.

For 97% of the 300,000 years of existence, our days consisted mainly of tracking, catching, killing, and preparing our sustenance. I’m sure there was something to do for “fun,” but it was likely reserved for children. Let’s continue.

- Navigation by sea didn’t start until 4000 years ago.

- The first roads seem to have been built around 4500 years ago

- Evidence of wheeled vehicles (carts and wagons) doesn’t emerge until 3500 years ago

If you wanted to go anywhere, you were walking. A pleasant walk in the park or a stroll after dinner is relaxing and fun, but most of us wouldn’t consider walking double or triple-digit miles fun.

People have this deluded idea that life should be fun and easy—or, at the very least, shouldn’t be hard—but life has always been hard. That’s only changed recently. Consider some things that we take for granted:

- The first automobile (using gas) wasn’t invented until 1885. (It is a common myth that Ford invented it later, but he merely created an assembly line)

- The first home refrigerators weren’t sold until 1913

- The first commercial flight didn’t fly until 1914

- The television was invented in 1927

- Penicillin wasn’t discovered until 1928 and didn’t become widely available for another decade.

- The microwave was invented in 1945

These inventions were all made a few decades before the computer, high-speed wireless internet, and cellular phones were invented. These inventions make life incredibly easy and fun, but we’ve only had this level of ease and comfort for less than 1% of our existence. Even the ability to cool your home with air conditioning didn’t exist until 1902.

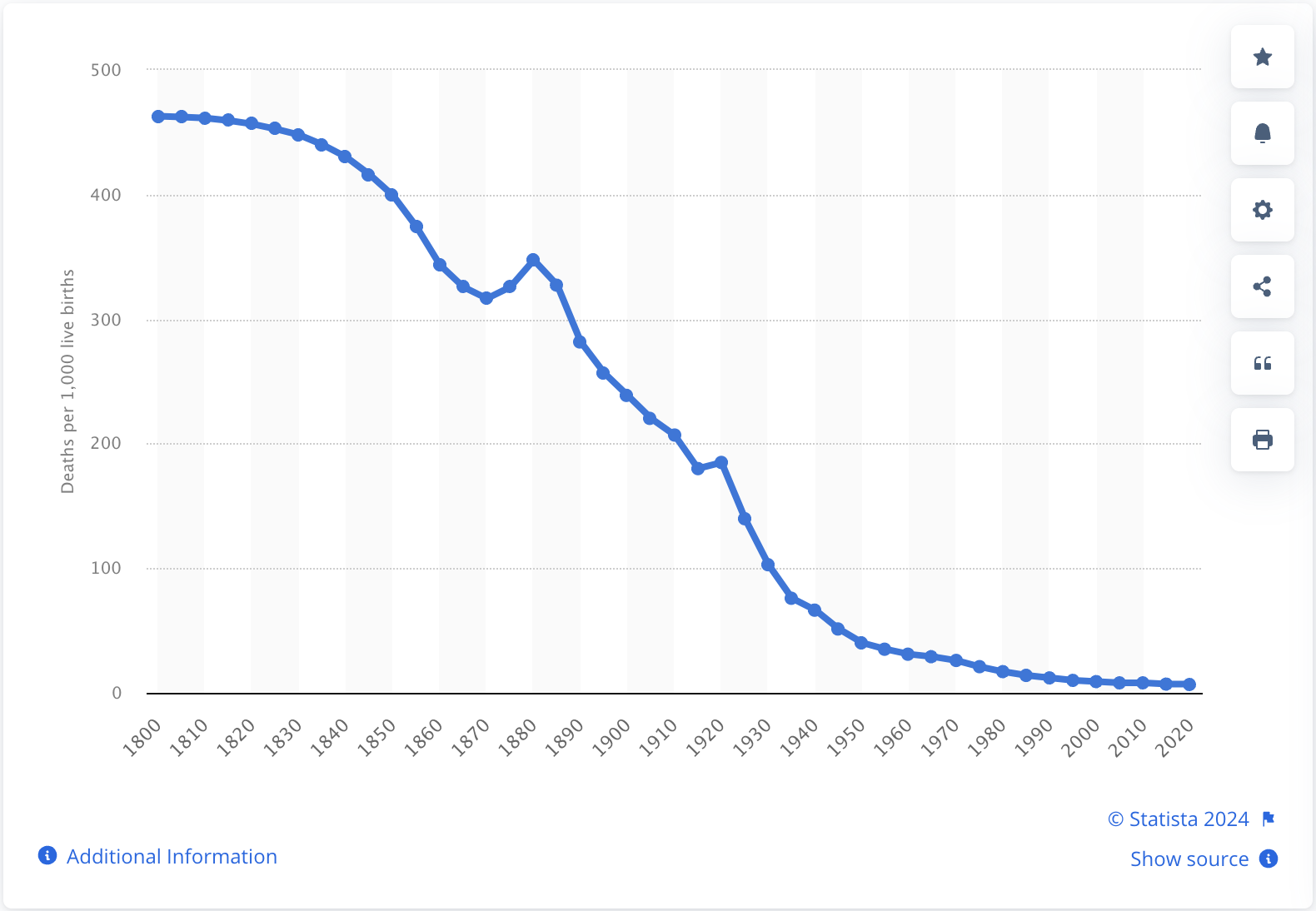

Most of our time on this planet has been misery. It was cold, challenging, and full of death. To put this reality into perspective, just 200 years ago, the child mortality rate (deaths for age < 5) in the United States was 46%. That’s almost a coin flip.

These were not happy times, but this was the state of things. We’ve eradicated so many hardships in the world that this number stands at less than 1%—and has been for almost 100 years.

Life is hard, and modern technology has made many people believe it shouldn’t be. This line of reasoning is problematic.

I’m not arguing that society should return to a time when survival was a full-time job and half of your children perished. I’m only reminding you that humans evolved to deal with harsh circumstances. Now that we’ve removed many of them, we’ve become weak and entitled, and perhaps worst of all, we’ve invented problems where there are none.

“Did you know that the first Matrix was designed to be a perfect human world? Where none suffered, where everyone would be happy. It was a disaster. No one would accept the program. Entire crops were lost. Some believed we lacked the programming language to describe your perfect world. But I believe that, as a species, human beings define their reality through suffering and misery. The perfect world was a dream that your primitive cerebrum kept trying to wake up from.”

-Agent Smith, “The Matrix” (1999)

The Epidemic of Absence also makes an interesting point about our immune system. The author proposes that our immune system evolved in a much dirtier world. Most of human existence lacked antibiotics, vaccines, refrigeration, pasteurization, antiseptics, or even knowledge of germs. Yet, we manage to survive and replicate—at least 46% of us, anyway.

Now that the world is incredibly clean and sanitized, the immune system has nothing to do. So, instead of tamping down, it starts to attack all sorts of innocuous—or necessary—things. Food allergies and autoimmune conditions make the list. And surely, to support his argument, the author shows that as a country’s GDP increases (leading to a high quality of life), so does its incidence of allergies and autoimmunity issues.

Just as our immune system rejects this perfect world, so does our psyche. Objectively speaking, in any metric of quality of life (material living conditions, leisure and social interactions, economic security and safety, governance and basic rights, natural and living environment), this is the best time in history to be alive—and it’s not even debatable for most of the world (especially anyone capable of reading this essay).

Now, we manufacture crises because we need something to fight against. We come back to the problem of avoiding bad experiences. Our psyche doesn’t do any better in utopia than our bodies do without exercise.

Developing a “thick skin” is a metaphorical way of describing becoming more resilient, mentally tough, and less sensitive to criticism, rejection, or adversity. It’s about maintaining composure, self-confidence, and emotional stability in facing challenges or negative feedback.

Thick skin is necessary if you want to survive in the world. Even in this modern landscape, with all our conveniences, humans are still human. People will hurt you, embarrass you, and sometimes simply ignore you. You can’t legislate away the darkness of human behavior.

You can’t build “safe spaces” to protect yourself from “microaggressions.” How you feel about the world does not change the fundamentals of human nature. You either learn to deal with life, or life deals with you.

Now, at this point, I have to make something clear. I’m not advocating for abuse, mistreatment, bullying, or any mistreatment toward one another. I’m a peace and love type of guy, but I can be a peace and love type of guy because I don’t expect everyone to be peaceful and loving.

When Roosevelt said to “walk softly and carry a big stick,” he was talking about international diplomacy, but the point also holds on a local personal level.

In other words, you need to be capable. Being capable means standing up for yourself and learning to control your emotions. To do this, you need to do hard things.

The beauty of doing hard things is that they typically kick your ass and drag your ego through the mud. But in suffering a setback, you become more rigid and more resilient. The moment you make your priority finding the easiest, most pleasurable way to make it through any situation, you have lost battle twice.

The first loss is immediate when you forfeit an opportunity to get strong. This loss will feel like a victory because you won’t suffer. The second loss you’ll suffer is the next time you face a similar (if not identical) situation.

You’ll be weaker and on your back foot, meaning that even if the problem has stayed at the same level, it’s effectively gotten stronger because you have now lost the initiative—and you’ve conditioned yourself to avoid it.