Identity and Connection: A Personal Journey Through Addiction

My name is Ed, and I’m an alcoholic. I’ve been sober since December 23rd, 2013. This wasn’t my first realization of being an alcoholic, nor was it my first attempt at sobriety.

I started drinking at seventeen, and my first attempt at sobriety lasted almost four years, from age nineteen to twenty-three. I tried again at twenty-four, making a dramatic show of dumping out all the alcohol I had hidden—in my backpack, cabinet, drawers, and car trunk—just in case of emergency.

After all, no one follows the Boy Scout model of “always be prepared” quite like an alcoholic.

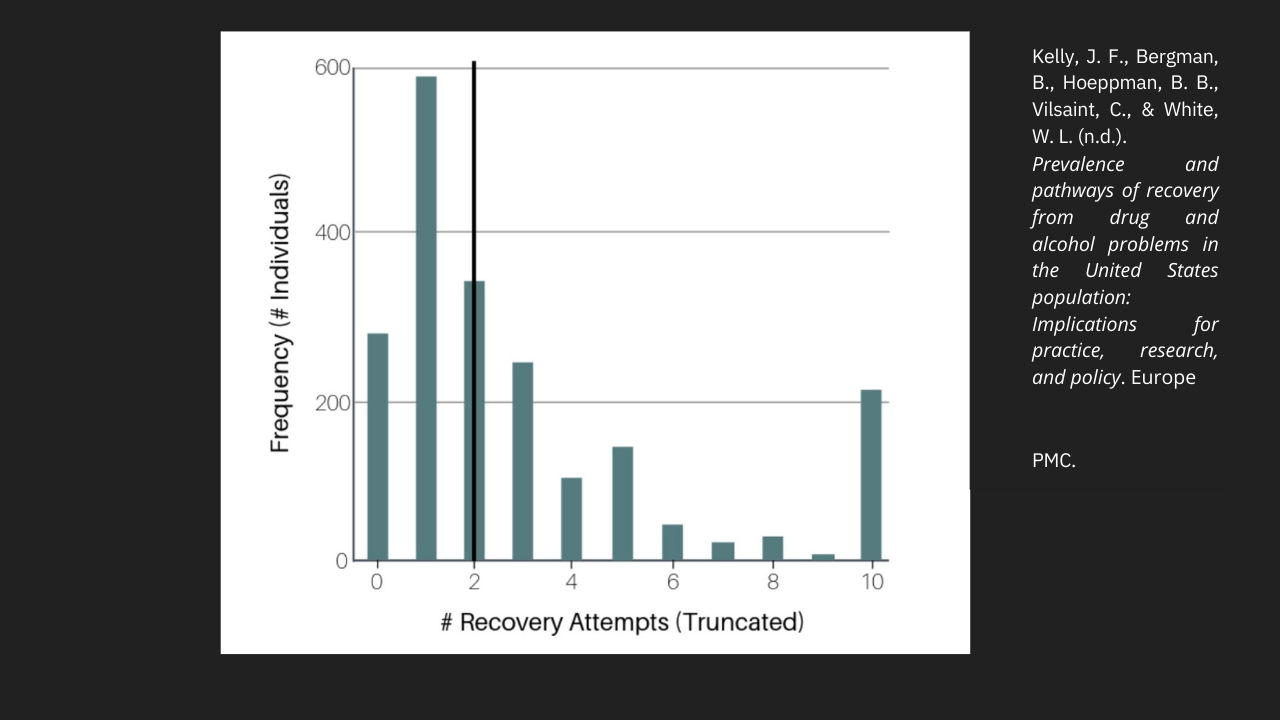

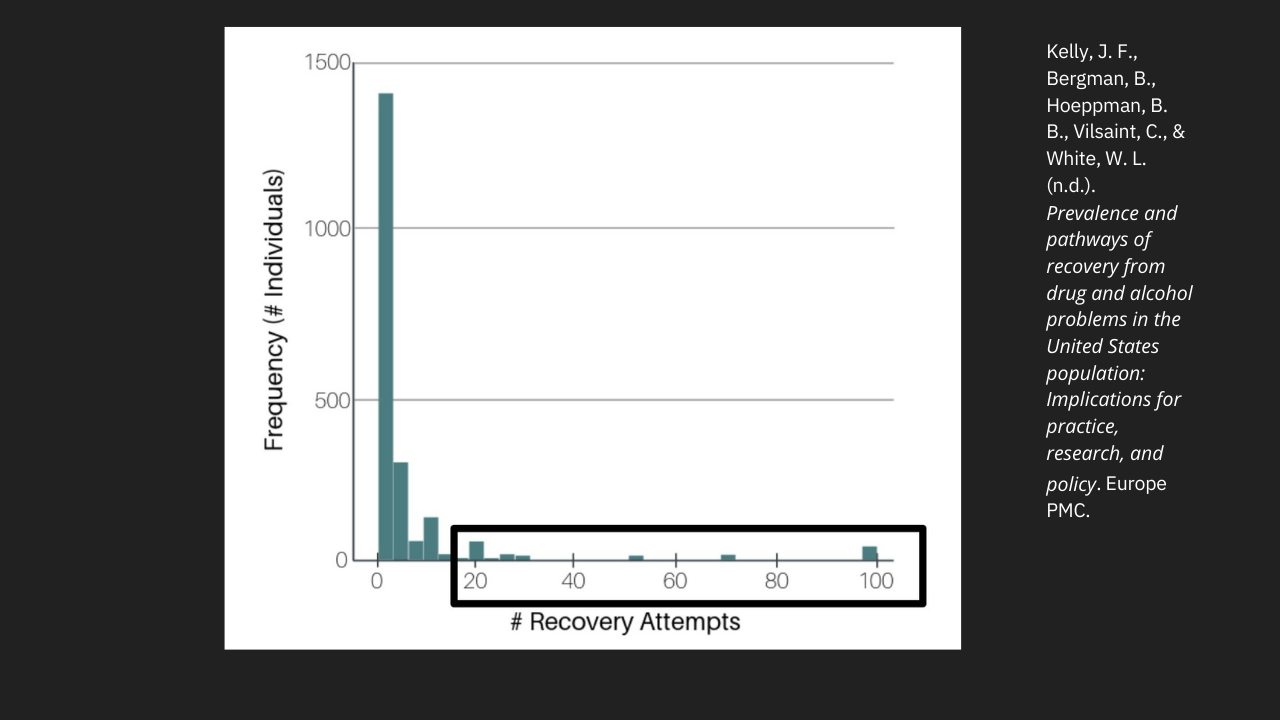

Over the next four years, I’d maintain sobriety for about thirty days before wiping it out in a weekend of binge drinking. This on-again-off-again pattern isn’t uncommon among those struggling with addiction.

According to the National Recovery Survey, people who acquire five or more years of sobriety needed an average of five attempts to maintain lasting recovery.

What’s most striking about these numbers is that they come from individuals who wanted to quit so desperately they kept trying, even after the fifth attempt—in many cases, even after the tenth.

My last temporary stint of sobriety lasted from June 4th to December 22nd, 2013. The night of December 22nd is one I’ll never forget—if I could ever fully remember it.

According to witness accounts, I went out drinking, got drunk, picked fights with multiple people, got thrown out of a bar, and wound up at a friend’s house with no recollection of how I got there. The only thing I knew was that I had driven. The next day, I attended a 12-step meeting and got back on the wagon. I’ve been a happy rider ever since.

What was different about that time that allowed me to stay sober, and how can we use it to help others not only get and stay sober but prevent addiction in the first place? The answer lies in understanding both the neurological basis of addiction and the role of identity in recovery.

I first realized I was an alcoholic in the summer of 2011 while living in Los Angeles as part of the All-American Heavyweight program. This program trained top-level amateur heavyweight boxers with Olympic aspirations. It was a dream come true—they covered my apartment, utilities, food, and provided a $4,000 monthly stipend. All I had to do was train and win fights.

However, I was incredibly lonely. With a suspended driver’s license, building a social life in Los Angeles proved nearly impossible. Depression led me to drink alone, attempting to recreate the good feelings I’d experienced drinking with friends back home.

Addiction is fundamentally driven by the dopamine reward system. Dopamine, a neurotransmitter in our brains, plays a crucial role in happiness and motivation. When anticipating a reward, your brain releases dopamine; achieving that reward triggers an even larger release.

This motivates you to repeat whatever caused the initial surge. However, continued drinking forces your brain to decrease dopamine receptor sensitivity, requiring more alcohol to achieve the same effect. Meanwhile, loneliness persists, driving further consumption in a vicious cycle.

As Johann Hari notes in his TED talk about the opioid crisis, “The opposite of addiction is connection.” When dopamine reward centers are damaged by substances, genuine connection becomes increasingly difficult. This problem is especially crippling when most of your social activities revolve around drinking—giving up alcohol often means losing social connections, creating an even larger void to fill.

After more than ten years and numerous attempts at sobriety, I finally found control by joining the Army. While this might seem like an extreme solution, it provided something crucial: forced sobriety combined with a new environment for identity formation.

Through basic training and Advanced Individual Training (AIT), I spent 26 weeks not just physically unable to drink, but meeting new people, gaining new skills, and building a new identity without alcohol in the background. It was the first time in my adult life that I could define myself positively and independently of alcohol.

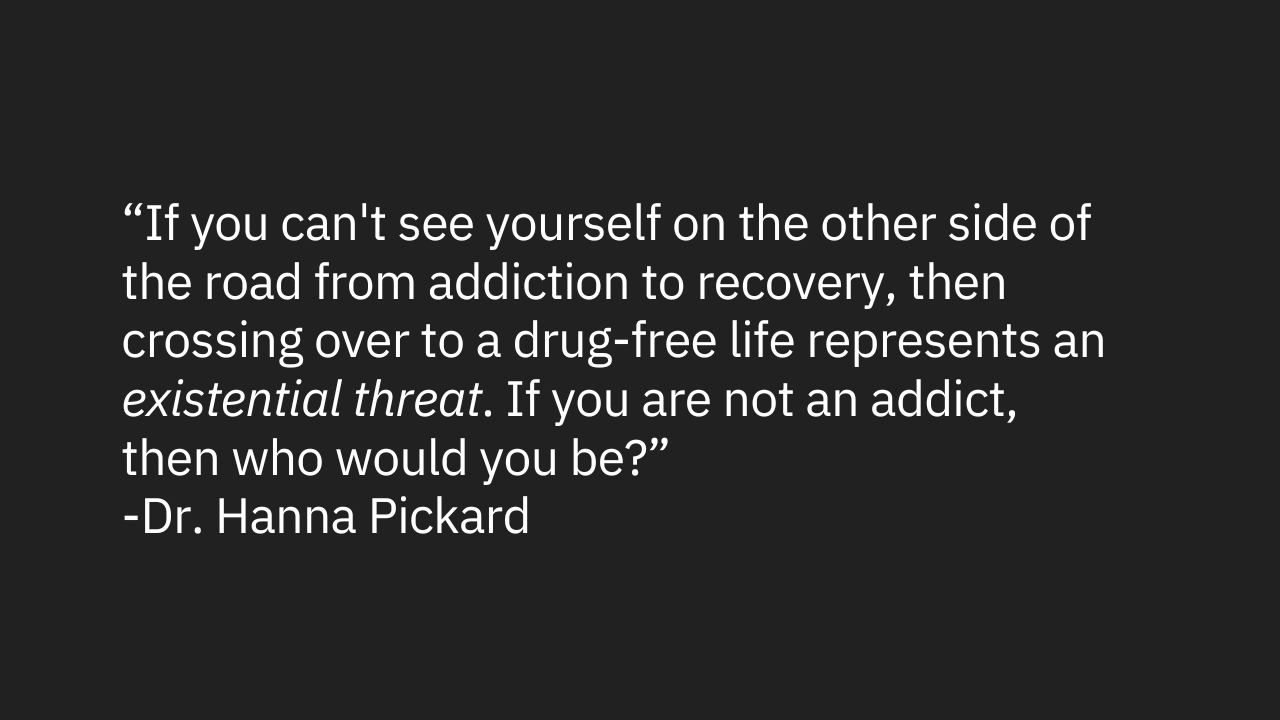

Dr. Hannah Pickard, a professor of philosophy and bioethics, emphasizes the importance of identity in addiction recovery. She notes that for addicts, imagining life without addiction represents an existential crisis—if you’re not an addict, then who are you?

After my final relapse, I immediately filled my life with activities that kept me away from my old environment while allowing me to build a new identity and connect with people who either didn’t know me as a heavy drinker or supported my change.

While loneliness and identity confusion aren’t the only factors in addiction, neurological studies, epidemiological research, and anecdotal accounts confirm their significant role.

The military isn’t necessarily the answer for everyone—it was simply my path to discovering the importance of identity and meaningful life changes. If you or someone you know struggles with addiction, addressing isolation and identity can be powerful starting points for recovery.

By focusing on these aspects, you may not just change a life—you might save one.