Watch the video version of this post below

On December 23rd, 2024, I celebrated 11 years of sobriety.

When I tell people my sobriety date, a lot of them ask me something along the lines of “How come you didn’t just make it a New Year’s Resolution? You know, wait until January 1st and enjoy the holidays?”

I’ve always found that response interesting for three reasons.

First, the question assumes that I was having fun drinking and should have prolonged that fun until the mythical January 1st day of resolution.

Anyone who’s ever struggled with addiction knows that while getting drunk or high certainly starts fun, by the time you’re going to basement meetings—or even considering that you have a problem in the first place—it’s moved WAY beyond a good time.

Second, the question demonstrates how intertwined alcohol is with our society.

The people who asked me couldn’t possibly imagine celebrating a holiday without different kinds of spirits and libations. I’m not saying that everyone who drinks alcohol is dependent on it or that they need it to enjoy their holidays. That’s—hopefully—not true.

But what I am saying is that alcohol—even now, with the sober living movement picking up serious steam over the last few years—is still considered such a vital element to celebrations that I’ve even had fellow recovering addicts ask me why I didn’t wait until January 1st.

Third, and the one most related to the topic of this video, is that most New Year’s Resolutions don’t work.

Only 9% of people stick to them, with 23% quitting in the first week and 43% quitting within the first month.

I was so bad with alcohol that I genuinely believe that if I continued drinking through Christmas, I wouldn’t have made it to the New Year. And, as the numbers point out, I wouldn’t have stuck with it either.

I doubt my relationship would have lasted without my decision to put down the bottle. This means I wouldn’t have my son.

I would have failed again at trying to learn math, meaning I wouldn’t have earned my degree in physics.

I definitely would have sabotaged my boxing career. I was already missing practices to drink or showing up drunk—which, by the way, is even dumber than it sounds…but not quite as dumb as drinking and driving, something else I regretfully did a lot of.

And, because I enlisted in the military to get money to go back to school in my 30s if I had eventually gotten a long overdue DUI, I would have not only had to deal with civilian justice but also military justice.

Who knows how my life would have turned out if I hadn’t stopped drinking, but I’m pretty sure it would have turned out at least as bad as my worst nightmares.

This isn’t a newsletter about getting sober.

It’s just that getting sober helped me to realize what the rest of this newsletter is about: if something is truly important, the worst thing you can do is wait until an arbitrary day of the year in the future to start fixing the problem, especially if that day has a historical success rate that is in the single digits.

Some of the people reading this will remember a TV show called “Intervention,” where addicts and alcoholics got an intervention from friends and family.

The loved ones told them all about how their addiction was ruining their health, hurting their children, costing them money they didn’t have, and how they were crashing out on life.

You’d think that all of these people showing love and issuing ultimatums like, “It’s the drugs or us!” would get these people to take a new path in life, but anyone who’s ever dealt with a crackhead family member knows already knows it doesn’t really go that way.

For everyone else who hasn’t had to confront theiri mother about her drinking habits, here’s a stat for you:

The success rate for classic drug intervention by family and friends is only 13%. That number goes slightly higher with trained individuals at the helm, but it never gets above 64%.

In other words, it doesn’t really work that way.

Let’s pause on “Intervention” for a minute and talk about another TV show, “The Biggest Loser.”

That show was a bit more popular so you probably remember it. If you don’t, the basic premise is that a group of overweight people would compete to see who could lose the most weight over the season. I watched a few seasons, and let me tell you—some of those changes were incredible. How incredible, you ask?

A report calculated the average weight of the contestants on the first week of the show—a whooping 328 lbs—then the average weight of the contestants after 30 weeks of filming—199 lbs. A 6-year follow-up found that the average weight of the contestants had shot back up to 290 lbs.

In other words, the average contestant gained back 75% of their lost weight.

So what the hell is happening, and how does it relate to sobriety and New Year’s Resolutions?

The problem with New Year’s Resolutions isn’t that you don’t want your life to improve.

You certainly want the benefits of being healthier, having more money, or overcoming addiction, but the real issue is that *not* having those things doesn’t hurt enough.

You know the problems are annoying and, in many cases, dangerous. Still, you’ve gotten so used to a comfortable mediocrity that you’d rather keep the short-term comfort by not committing to a long-term vision of your best self than make challenging changes that hurt in the short-term but dramatically raise the baseline of your living experience for the rest of your life.

This is why interventions fail.

Nothing can force people to change if they aren’t ready or genuinely interested in making changes. You can lead a junkie to rehab, but you can’t make him follow the steps—and that’s exactly what a New Year’s resolution is trying to accomplish.

It’s an external intervention. It isn’t motivated by your genuine desire; it’s motivated by societal pressure to make changes because it’s January 1st. Because that’s the day everyone has randomly decided to try and make important changes to their life, you just go along with it.

Maybe you feel like having a start date, the momentum of the new year, and a host of expectations will help things stick, but it never goes this way. Well, it never goes this way 91% of the time. And why?

Because if changes you need to make were actually important to you, you wouldn’t wait until January 1st.

When I had a drinking problem, I didn’t wait for some magical future date to fix it. When I realized things were going wrong, I took immediate steps to get sober.

The events that made me realize I had a serious problem happened to take place the night of December 22nd, with Christmas two days later and New Year’s nine days after that, but that was just a coincidence.

If I had woken up at a friend’s house with no idea how I got there other than knowing I drove because my car was there, with no recollection of the previous night’s foolery in August or March, then the sobriety date would have lined up with the Labor Day, easter, or St. Patrick’s day.

But my sobriety date being so close to New Year’s helped me understand something: most people don’t stick to their New Year’s resolutions because they don’t truly want to make those changes.

Internal desire is the first thing required for change to happen. When you really want to change, nothing can stop you. However, as statistics from interventions, resolutions, and even shows like The Biggest Loser demonstrate, if it’s not internally motivated, you either won’t make the change or, if you do, you won’t stick to it.

You’ll have committed to a goal without really committing to it.

So why don’t people care enough? From my experience with sobriety, there are two main reasons.

First, I needed to hurt enough. I had tried getting sober before, with many relapses and half-hearted attempts. What made it stick eleven years ago was that I finally hit my personal rock bottom.

Everyone needs to have a personal point where enough is enough, but if you don’t have that, you’ll keep falling until society determines your rock bottom, and that’s either behind bars, on a cot at a homeless shelter, or dealing with so many health problems that you can’t even walk up a flight of stairs without feeling you were in a 12 round fight.

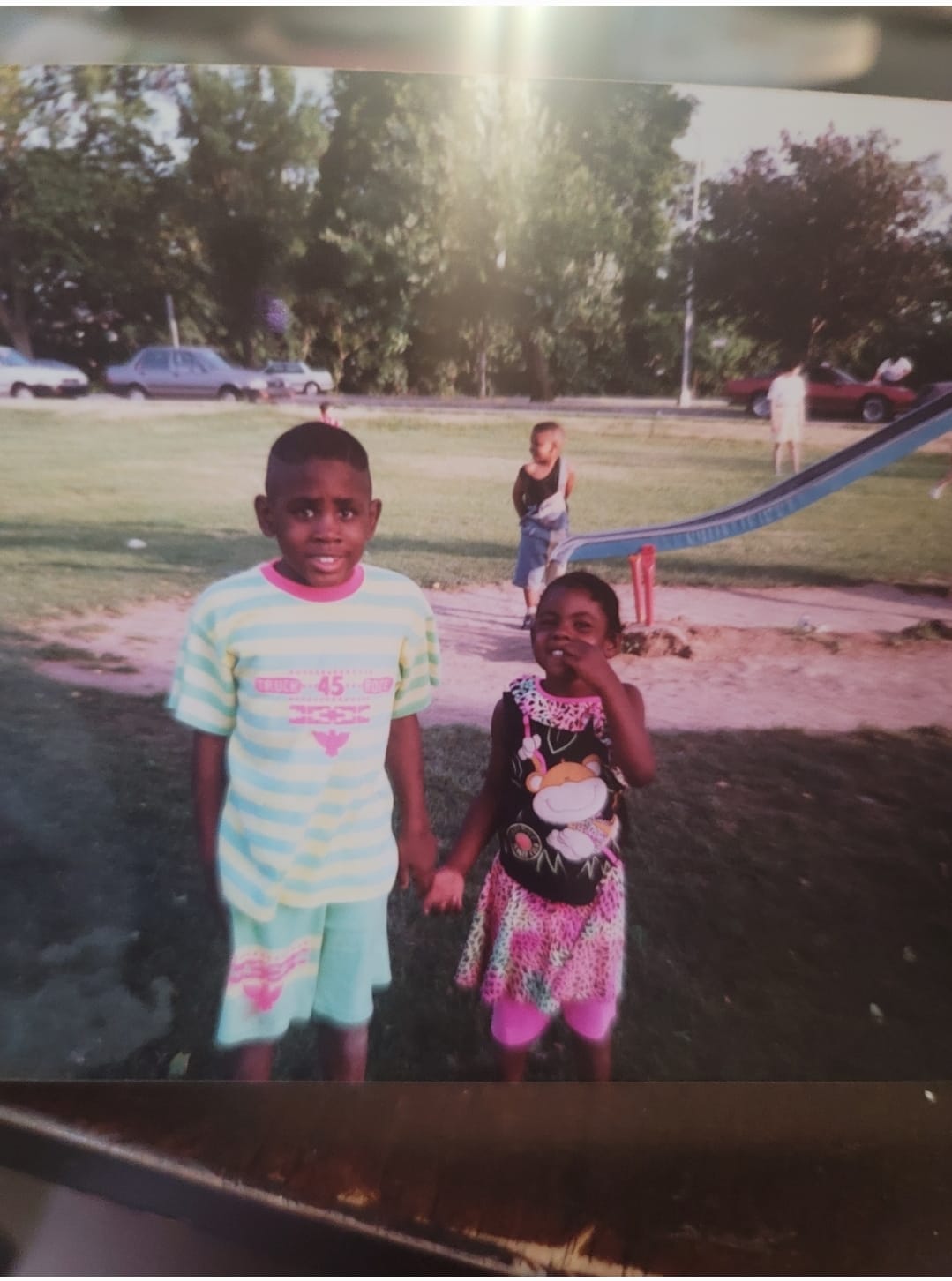

But it wasn’t just about hitting my personal rock bottom. One of the things sobriety helped me to realize was that I didn’t think highly of myself at all. I still had the mentality of an abused and bullied kid from the ghetto who was looking to feel loved and accepted.

The feeling of fitting in and being like drove a lot of addiction and self-destructive behavior.

But a series of changes in the year 2013 helped me finally stick with sobriety. I had started to value myself through a series of positive life changes:

- I had enlisted in the military

- I had just met the mother of my son.

- The reason I enlisted in the army was to get the funds necessary to give college one more try in my 30s

- I had turned professional in boxing after a stellar amateur career despite my drinking problems.

These accomplishments alone didn’t change my drinking habits. In fact, I’d previously used my success in boxing to deny my alcoholism.

If I could knock dudes out, get nationally ranked, earn sponsorships, and still throw back a box of wine a night, I figured there wasn’t anything you could say to me.

It was a coping mechanism, but as far as those go, it was much better than just telling people to shut up and mind their own business.

But this time was different because I felt like I finally had something to lose. I had real goals and was surrounded by people who would hold me accountable for my drinking.

First, it was my boxing coach, Tom Yankello. The guy doesn’t drink or smoke and lives in total commitment to boxing. He was the first person to call me out, yell at me, and basically call me a low-quality human being for my drinking habits.

I’m not saying this is the method that everyone needs—and it didn’t work immediately—but it was the first time in my life someone not only told me that I was messing up but lived the same standard.

I didn’t start training with Tom until I was 27, but it was the first time I felt like an adult male cared about me. Men can have daddy issues too, and lack of personal standards is a big one for cats who a single mom raised like I was.

Looking at my behavior before and after sobriety, the biggest difference wasn’t just being sober—it was that I finally felt I had something meaningful to lose. I had put myself in an environment where my drinking would have real consequences.

When I first met my wife, I thought, “This is a really nice girl. I don’t wanna expose her to all of my drunken nonsense.” Previously, I would have just bounced out on the relationship, telling myself that we were incompatible because one of my favorite go-to lines for justifying my drinking was, “If you don’t like me drunk, you wouldn’t like me sober.” However, I had grown just enough by this point in my life that I knew how much bullshit that was.

Because being in love is neurochemically similar to being on drugs, I didn’t want to risk getting this girl hooked on a loser. But I didn’t wanna leave her either, because I thought she was good for me and she liked me for me—because I damn sure ain’t have any money back then.

So my decision was simple. I could either leave her or stop drinking, but I had enough of a conscience to know that doing both was unacceptable. When someone cared about me unconditionally, knowing my flaws and weaknesses, it made me want to become better.

With my boxing and attempt at school, I realized I could have a successful life, or I could drink, but I couldn’t do both effectively. While some people can manage both, I had to accept that I wasn’t one of them.

In my next life, I’m gonna be a rock star or something so I can party and still make bank, but I wasn’t born with those gifts (or curses, I suppose) in this lifetime, so this was another push toward sticking with sobriety.

All of these are great reasons, but I’ve gotta thank the military for giving me a chance to see that I could be someone interesting and likable outside of booze.

Now, I hadn’t enlisted in the army to get sober. I did it to escape the mess my life was slowly becoming. Getting money for school was a big reason, but I also needed money, in general, because I was going broke—fast.

It just so happens that I couldn’t drink during training. I did ten sober months of basic training, followed by 16 sober weeks of “advanced individual training” or “AIT.”

I tell people that basic training is like prison without the violence, and AIT is like college without the booze.

So, for 26 weeks, I had sobriety forced upon me. But this time was different from my other attempts, not just because I was physically unable to drink, but because I was meeting new people, gaining new skills, and building a new identity without alcohol. It was the first time in my adult life that I was able to define myself positively and independently of alcohol.

My identity shifted from someone who made friends under the influence of alcohol to someone who earned respect through my conduct in the military and other areas of life.

I learned the difference between being liked and being respected. When trying to be liked, you often do things that aren’t good for you. But when you pursue respect—real respect, not the street kind—it keeps you on a solid path.

A resolution or external pressure didn’t drive my journey from alcohol to sobriety—it came from a deep personal need for change and a genuine desire to protect what I had built.

This fundamental difference between internal motivation and external pressure brings us to the heart of why most people struggle with their goals and aspirations.

This is why resolutions fail: you don’t hurt or want it badly enough, or both. You haven’t truly identified what failure looks like. It’s easy to imagine success—the big house, money, dream body—but you need to imagine your life if you don’t succeed. That can be far more motivating.

People get comfortable in mediocrity because it’s not bad enough to force change. My physics professor once said, “All organisms assume the most energy-efficient configuration.” We all naturally take the most efficient path, trying to get the most reward for the least effort. This becomes problematic when that minimal effort keeps you in a state of subpar existence.

You have to hate where you are so much that staying the same becomes impossible. You need to choose your rock bottom before reality chooses it for you.

It’s like that scene in The Matrix when Trinity tells Neo, “You’ve been down that road before, and you know how it ends, and you don’t want to be there.”

You’ll see why New Year’s resolutions are meaningless when you understand all this. If something is truly important, you’ll act immediately.

If you broke your leg on December 1st, you wouldn’t wait until January 1st to fix it because it’s part of your resolution. That’s the urgency you need to approach your problems with.

When you develop this mindset, you’ll never need New Year’s resolutions again. You’ll see them for what they are: externally pressured, socially reinforced commitments that rarely result in lasting change because the people making them don’t truly want to change. But you will be different.

Watch this video so you can understand just how serious not fixing your alcohol problem could be for you.