I recently had a consultation call with a client. We discussed whether he should go home to India to be closer to his family and accept an arranged marriage or stay in the United States and try to meet a woman and build a life.

I told him to imagine the worst-case scenario of each path. Whichever one he could more easily endure, that was the path he should go with.

You could stop reading this email right now, and you’d have enough to change your life. I truly believe that.

However, the rest of this newsletter will explain my reasoning and hopefully give you a useful framework for solving problems in your own life.

We need to cover a vital idea: expected value (EV).

Expected Value Made Simple

Those of you with a math or gambling background will already be familiar with this idea, but the following primer is for everyone else. Don’t worry. I’ll keep it short and simple.

Also, you won’t need to crunch any numbers. My goal is to give you an intuitive grasp of the idea so you can use it to win bigger in life–not to give you a crash course in probability theory.

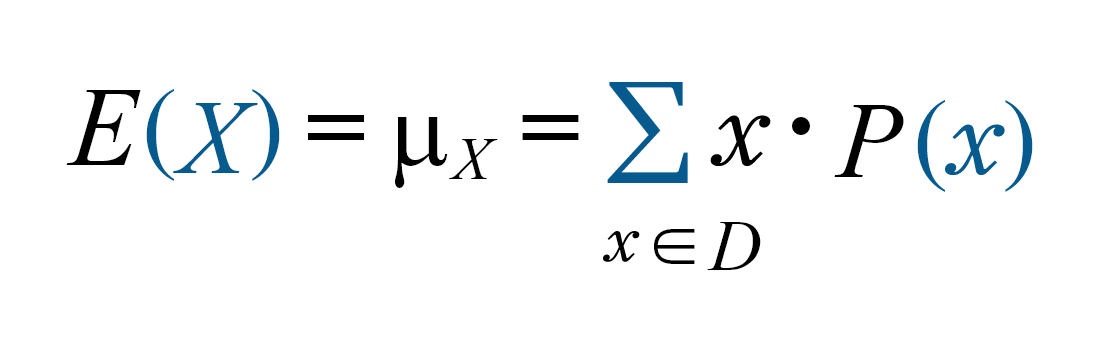

The expected value of an event is the weighted average of the values of the outcomes of the given event. This isn’t exactly what defines EV, but it’s useful enough for us to use it to improve our lives by improving our decisions.

Warren Buffet described this idea best:

“Take the probability of loss times the amount of possible loss from the probability of gain times the amount of possible gain. That is what we’re trying to do.”

Parking tickets are the simplest example we can use.

The cost of parking outside your favorite breakfast spot is $3 (expensive, sure, but the numbers don’t really matter). The meter maid rarely comes by, so you could just skimp on paying the $3 most days.

However, if you get caught parking without paying, you pay a $300 fine–and in this scenario, that money is due instantly, or you lose your car forever.

Real-life events inspire this example. When I was 23, I got a boot on my car. It cost $800 to get off, and I had to pay it all at once. Otherwise, my car would be towed to the impound lot (at additional cost), and each day it was there, it would cost me an additional $110.

If I didn’t retrieve my car in two weeks, I would be charged for the destruction of the car and all the other fees. Fortunately, a friend loaned me the money, and I got my car back before any extra juice kicked in.

Generally speaking, to most people, this is a no-brainer problem. Consider what can happen if you don’t pay the meter. The few times you get away with it are not worth what happens the one time you get caught. This event has a negative expected value.

If you cough up the $3 every time you park, the worst-case scenario is that you’re out $3. That’s a lot less than $300 and the potential loss of a vehicle that could cost you at least 5 figures. This event has a much lower negative value.

The idea is all that matters: the second event is less painful than the first.

You won’t get caught often, but if you do, it will sting. So what should you do? Well, that depends on how bad the sting is to you.

A New Way Of Looking At Making Decisions

If you’re like most people, a surprise $300 is enough to at least make you angry. If it happens twice or thrice in the same month, you might have a real financial problem on your hands.

Even if you parked there every day, you could much more easily deal with the slow burn of $3/day over a month than a $300 due all at once.

Expected value is another way of looking at the same question I posed to my client. If things don’t go well, how bad can they get, and which “worse case scenario” is preferable?

I didn’t focus on the upside because the idea is that my client would be happy with the best-case scenario in either path. That’s why we’re making the comparison in the first place. After all, if only one path had a downside, then we wouldn’t entertain it as a choice.

We focused on the downside because it’s a possible–and, in many cases, highly probable–outcome.

Murphy’s Law states that whatever can go wrong will go wrong. While I’m not nearly that pessimistic (plus I understand the concept of expected value and probability), I believe this is an excellent hedge against making the wrong decision.

It’s better not to be wrong most of the time than to be right only some of it.

Crashing Airplanes and Catastrophic Events

This is one of many reasons why airplane safety is such a big deal.

The worst-case scenario is death–and there really isn’t an in-between. Flying is so safe that if you try to calculate the odds of any given flight crashing (simplistically, the number of crashes divided by the total number of flights), you get a number so small that most calculators simply return a “0”.

In other words, the EV of a plane crash is so bad that it can’t be allowed to happen–and when it does, it’s (rightfully so) big news. Compare that to the number of automobile crashes and people who die as a result of them for any given year.

I find it hilarious that *far* more people are afraid of flying than driving, considering that you effectively have no chance of dying from a plane crash. Meanwhile, your odds of dying in a car accident hover between 1 and 4 in 10,000 (.0001-.0004).

Those aren’t exactly huge odds, but all calculators will return a value for “1/10000.” Furthermore, so many different things can temporarily increase those chances (weather, other drivers, events) that are non-factors in flight.

Most decisions you make won’t have a downside as bad as death, but for the ones that come close, you should do whatever you can to reduce the odds of it happening.

For example, there’s no good reason not to wear a seatbelt, text, or drink while driving.

Nothing Is Guaranteed—Except Death

This is an idea that is fundamental to making the right decisions in your life. There is no such thing as a guaranteed outcome.

The best thing you can do is make every little decision have a positive expected value. If given two choices, focus on the one with a higher negative expected value. If you do this, you’ll be in a good position when things go wrong.

And while things don’t always go wrong, they do often enough (especially when they shouldn’t) that you need to account for that possibility in your decision-making process actively. When in doubt, focus on the choice that leaves you in the best position if you come up on the wrong side of things.

Don’t miss another issue!

I’m a former heavyweight pro-boxer (13-1-1) and alcoholic (Sobriety date 12/23/13), current writer, and aspiring chess master. I was raised in the projects by a single mom and failed high school, but I eventually earned a bachelor’s degree in Physics.

Follow me X (Twitter), LinkedIn, Youtube, or Instagram. Subscribe below to the Stoic Street Smarts newsletter to never miss an issue.

More Stoic Street Smarts Newsletters!